HIGHER FOR LONGER—UPDATING OUR TREASURY FORECAST

U.S. Treasury yields have seemingly been moving in one direction lately (higher), with the 30-year Treasury yield temporarily breaching 5% for the first time since 2007. The move higher in yields (lower in price) has been unrelenting, with intermediate and longer-term Treasury yields bearing the brunt of the move. There are several reasons we’re seeing higher yields, but rates are moving higher alongside a U.S. economy that has continued to outperform expectations, pushing recession expectations out further, and by the unwinding of rate cut expectations to be more in line with the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) “higher for longer” regime. And with the economic data continuing to show a more resilient economy than originally expected, we think Treasury yields are likely going to stay higher for longer as well. As such, we now project the 10-year Treasury yield will end the year between 4.25% and 4.75% (previously 3.25% and 3.75%).

THE (SURPRISINGLY) RESILIENT ECONOMY

Coming into the year, and further outlined within our Midyear Outlook 2023: The Path Toward Stability, our baseline forecast was for the domestic economy to slide into recession in late 2023 as consumer demand cooled, especially for services. Moreover, the economic slowdown, we thought, would likely keep the Fed from aggressively hiking short term interest rates and originally modeled out a year-end fed funds rate of 4.5%. In that scenario, we expected the 10- year Treasury yield to end the year between 3.25% and 3.75%. However, the economy has been more resilient than expected, and the Fed has taken the fed funds rate to 5.5%, while further indicating rate cuts would not likely happen anytime soon. This “higher for longer” narrative from the Fed has kept Treasury yields higher as well and, absent a broader macro event, will likely keep Treasury yields higher for longer too.

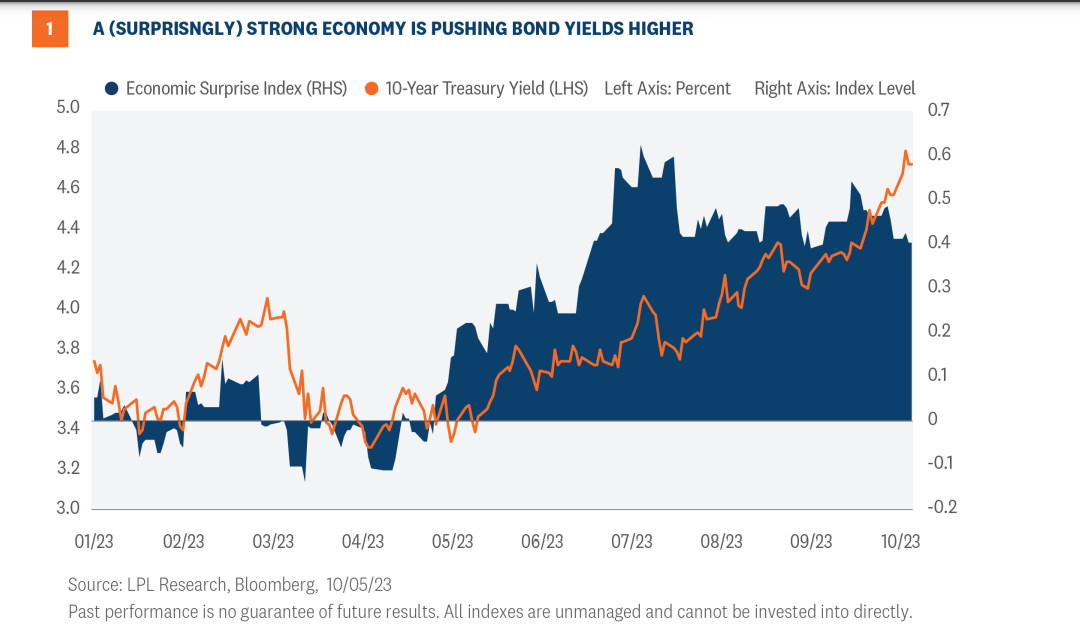

While there has been noticeable weakness in the most interest rate-sensitive parts of the economy, most notably housing, the broader economy has been surprisingly resilient despite an overly aggressive Fed. Figure 1 compares the Bloomberg Economic Surprise Index and the 10-year Treasury yield. The index includes economic data on things like the labor market, retail sales, and the personal/household sector, to name a few. And since May, the economic data, broadly, has surprised to the upside, pushing out prospects of an economic slowdown, which has pushed Treasury yields higher as well.

PRICING OUT NEAR-TERM RECESSION RISKS

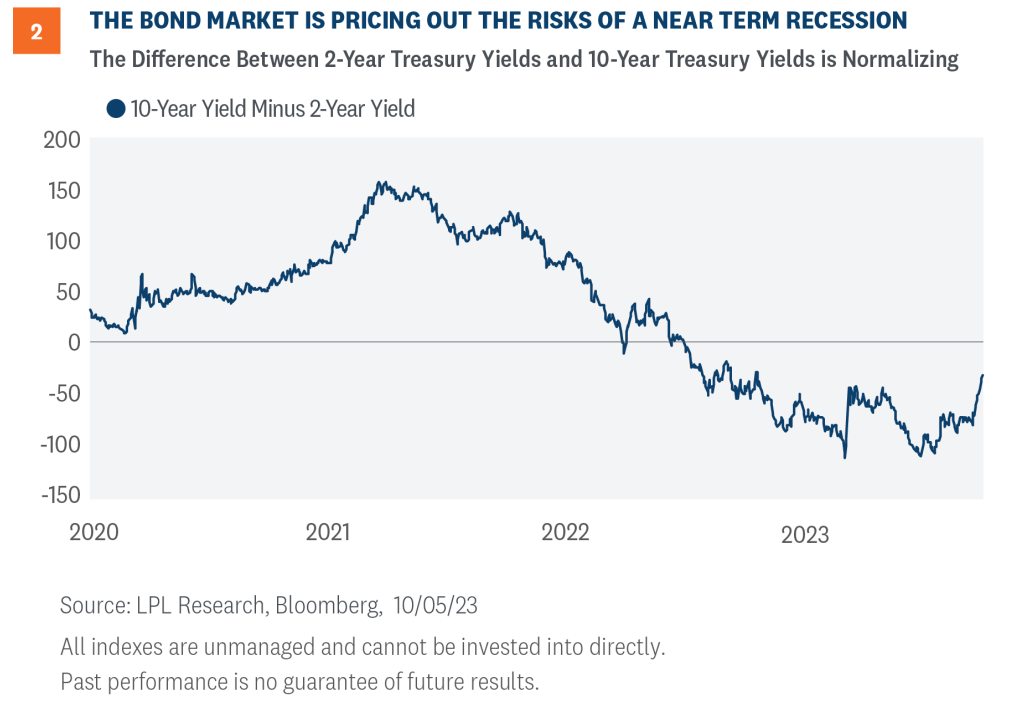

The shape of the U.S. Treasury yield curve is often looked at as a barometer for U.S. economic growth. More specifically, it reflects how the Fed intends to stimulate or slow economic growth by cutting or raising its policy rate. Each tenor on the curve is roughly the expected policy rate plus or minus a term premium (the term premium represents the expected compensation for lending for longer periods of time). In “normal” times, the yield curve is upward sloping, meaning longer maturity Treasury yields are higher than shorter maturity Treasury yields. However, when the expectations of an economic contraction increase, shorter maturity securities could eventually out-yield longer maturity securities as expectations of Fed rate cuts push longer maturity bond yields lower, which serves to invert the yield curve.

As the economic data has continued to surprise to the upside, however, the bond market’s yield curve has slowly started to dis-invert (Figure 2). After spending over a year inverted and reaching levels last seen in the 1980s, the difference between shorter maturity Treasury yields and longer maturity yields is normalizing. And while that difference has narrowed, there is still a risk to Treasury yields that the gap fully normalizes, which could put additional upward pressure on intermediate and longer-term yields.

BUYER STRIKE COMING?

If hoping the Fitch downgrade would serve as a wake-up call to Washington, it hasn’t. Since the debt ceiling debate was resolved back in June, the Treasury Department has steadily increased the amount of Treasury debt outstanding. As of September 30, total debt outstanding stood at a record $33.2 trillion, which is up from the $31.5 trillion right before Congress gave the Treasury Department unfettered borrowing capacity until January 2025. Now, to be fair, only $26 trillion of that is held by the public (with the rest held within the U.S. government). But the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expects total Treasury debt held by the public to grow to over $46 trillion by 2032. The primary reason for the increase in expected debt issuance is an increase in spending. Per the CBO, the U.S. government is expected to run sizable deficits over the next decade to the tune of 5%–7% of GDP each year. So, to fund those deficits, Treasury needs to issue debt at the same time the largest owners of Treasury securities (the Fed, Japan, and China) are generally reducing their impact in the Treasury market.

However, as long as Treasuries are considered risk-free securities, there will always be buyers. Full stop. The question though remains price. At what price would it take for nontraditional buyers to get interested? So far, we haven’t seen a drop off in interest during Treasury auctions, but there could be an eventual fatigue, which would mean yields would need to increase (or at least stay elevated) to attract that additional demand.

TECHNICAL ANALYSIS BACKDROP FOR RATES

As shown in Figure 3, 10-year yields have broken out above the October 2022 highs at 4.34%, leaving 4.70% and 4.90% as the next areas of resistance. Momentum is confirming the breakout, but yields are now historically overbought. The Relative Strength Index (RSI)—a momentum oscillator used to measure the speed and magnitude of price action—climbed to 73 two weeks ago, marking its highest reading in nearly a year.

Traders are also positioned for higher yields as short positions in 10-year Treasuries remain near record highs. The most recent Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) data shows total short positions among leveraged funds (typically hedge funds or speculators) reached 1.7 million contracts last month, coming in just below the record-high of 1.8 million contracts in May. It is important to note that extremes in futures positioning are often found at major inflection points and are commonly used as a contrarian indicator. Given the degree of overbought conditions, and the potential for some short covering, yields appear vulnerable to a short-term pullback and/or consolidation phase; however, the longer-term trend for now is up.

CONCLUSION

Bottom line, the move higher in Treasury yields has been unrelenting, with intermediate and longer-term Treasury yields bearing the brunt of the move. Economic growth has continued to surprise to the upside, which could allow the Fed to keep short-term interest rates elevated for longer. Additionally, the Treasury yield curve remains inverted so as the probabilities of a recession continue to get priced out, we could continue to see the prospects of a more normal, flat, or even upward sloping yield curve, which would mean 10-year yields could move higher still.

The Treasury Department is expected to issue a lot of Treasury securities to fund budget deficits and with the potential for the Bank of Japan to finally end its aggressively loose monetary policies, we could continue to see upward pressure on yields. However, while supply/demand dynamics can influence prices in the near term, the long-term direction of yields is based on expected Fed policy. So, unless the Fed isn’t done raising rates due to a resurgence of inflationary pressures (we don’t think that is likely) the big move in yields has likely already taken place. Inflation is trending in the right direction and the Fed could be near the end of its rate hiking campaign. That doesn’t mean rates are going to fall dramatically from current levels though, and that is fine for the longer-term prospects for fixed income investors.

Our base case is the economy slows toward the end of the year and into 2024 so that could take pressure off yields, which is why we think the 10-year Treasury yield ends the year between 4.25% and 4.75%. But in the meantime, momentum is in the driver’s seat.

INVESTMENT IMPLICATIONS

With yields back to levels last seen over a decade ago, we think bonds are an attractive asset class again. There are three primary reasons to own fixed income: diversification, liquidity, and income. And with the increase in yields recently, fixed income is providing income again. Right now, investors can build a high-quality fixed income portfolio of U.S. Treasury securities, AAArated agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and short maturity investment grade corporates that can generate attractive income. Investors don’t have to “reach for yield” anymore by taking on a lot of risk to meet their income needs. And for those investors concerned about still higher yields, laddered portfolios and individual bonds held to maturity are ways to take advantage of these higher yields (LPL advisors: make sure you check out the corporate credit focus list for individual credit names that may be worth a look).

LPL’s Strategic and Tactical Asset Allocation Committee (STAAC) recommends a neutral tactical allocation to equities, with a modest overweight to fixed income funded from cash. The risk-reward trade-off between stocks and bonds looks relatively balanced to us, with core bonds providing a yield advantage over cash.

The STAAC recommends being neutral on style, favors developed international equities over emerging markets and large caps over small, and maintains energy and industrials as top sector picks.

Within fixed income, the STAAC recommends an up-in-quality approach with benchmark-level interest rate sensitivity. We think core bond sectors (U.S. Treasuries, agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and short-maturity investment grade corporates) are currently more attractive than plus sectors (high-yield bonds and non-U.S. sectors) with the exception of preferred securities, which look attractive after having sold off this spring due to stresses in the banking system.